Did you know that around 300,000,000 tons of plastic waste is produced every year? Maybe looking into mushroom fungi for eating plastics isn’t such a bad idea.

That’s a lot of plastic garbage, and it has to go somewhere. Yes, there are mushroom fungi benefits to humans. Yes there are plants that eat plastic. Unfortunately, that “somewhere” that the plastic garbage ends up is in our shared environment, particularly the ocean, where about 10 million tons of biodegradable plastics ends up every year, causing the deaths of well over a hundred thousand marine creatures annually, and those are just the ones we know about.

➢ Read about mushroom fungi facts on the Quality Spores blog.

Benefits of Fungi and Plastic Eating Mushrooms

Perhaps, as with so many other situations, fungi can come to the rescue. In today’s post we’ll talk about the benefits of fungi and take a look at what researchers have discovered and what challenges must be overcome to put this knowledge to good use. But let’s also take a moment to establish why such a discovery is so important and learn about plastic eating mushrooms in this plastics recycling journey.

Recycling & Plastic Alternatives are Good, But Plants that Eat Plastic Is Still Not Good Enough

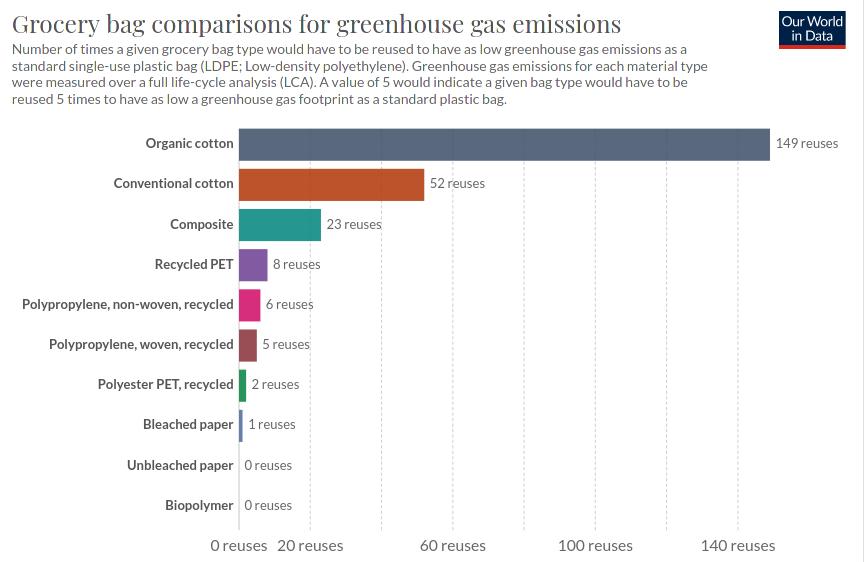

The answer to the plastic problem, most people would think, is to recycle or utilize the different mushroom fungi types for cleaning up the environment. There are indeed plants that eat plastic. But recycling plastic is difficult, expensive, and in some cases can even do more harm than good. After all, energy must be expended to recycle the plastic, which can be more costly to the environment in aggregate than the reuse of the plastic itself. Consider that it costs around $4,000 to recycle 1 ton of plastic bags. The resulting product can be sold for about $32. Obviously, this isn’t an attractive investment, nor is it viable long-term.

Mushroom Species That Can Eat Plastic

➢ There are mushroom species that can eat plastic.

Plastic alternatives present their own set of issues. An excellent lecture about the misconceptions about plastic alternatives was given in the 2013 TED Talk Paper beats plastic? How to rethink environmental folklore by Leyla Acaroglu. Furthermore, consider that a single-use low-density polyethylene plastic bag can actually have less overall impact on the environment than many popular plastic alternatives:

So what’s to be done? Since plastic is non-biodegradable—it’s estimated that a single polyethylene terephthalate (PET) soda bottle would take 500 years or more to break down—recycling and alternatives when used properly are good, but perhaps not good enough in the long run. Ultimately, we’re going to have to figure out a way to break down plastic faster.

Mycoremediation – Removing Pollutants From The Environment Using Fungi

The answer, as it turns out, may come in the form of mycoremediation, the process of removing pollutants or waste from the environment using fungi.

Meet Aspergillus Tubingensis, The Fungi That Eats Plastic and Breaks Down PET

In recent years, scientists have discovered a variety of biological organisms capable of breaking down plastic. The larval worm state of the wax moth was found to be capable of breaking down polyethylene, which makes up roughly 40% of all plastic waste globally.

Value of Fungi & Biodegradiation

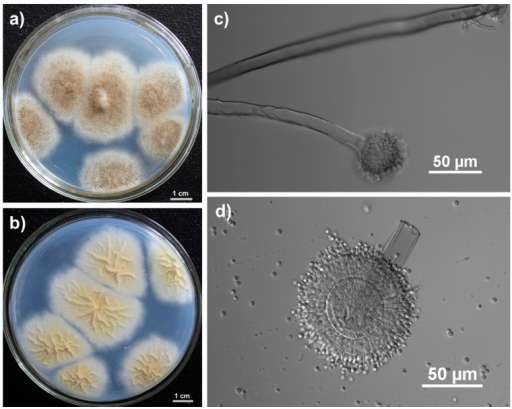

Further proving the undeniable value of fungi, one of the latest members of this plastic-eating lineup was discovered in 2017 by researchers at the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Kunming Institute of Botany.

In the paper Biodegradation of polyester polyurethane by Aspergillus tubingensis, researchers confirmed that Aspergillus tubingensis secretes an enzyme which disrupts the molecular bonds of plastic and subsequently separates them once its mycelium begins to colonize.

Leaching Heavy Metals From A Garbage Dump

This fungus has such powerful mycelium that it was later shown in 2020 to be capable of leaching multiple heavy metals from a soil column.

What makes Aspergillus tubingensis so interesting is that the researchers used plastic waste from an actual garbage dump—in other words, it was a real-world sample of plastic, not a controlled, specific material. The other key component is speed; Aspergillus tubingensis is capable of breaking down plastics entirely in mere weeks. As we’ll learn below, speed and scalability are critical components of putting this knowledge to use in a practical way.

The research team is currently exploring ways to support this method of mycoremediation by providing the fungi with ideal conditions, like temperature, culture mediums, and pH levels.

This could pave the way for using the fungus in waste treatment plants, or even in soils which are already contaminated by plastic waste.

Dr. Sehroon Khan, via Agroforestry World

We Know Plastics Can Be Enzymatically Broken Down; The Issue is Speed and Scalability

The big problems with using enzymatic biotechnology to break down plastic can be summed up in two words: speed and scalability.

Recall for a moment the wax worms mentioned above, capable of breaking down polyethylene. Researchers discovered this capability by placing 100 of the worms on a polyethylene plastic bag. Over 12 hours, about 3% of the bag was broken down.

While interesting, the problem is scale: 900,000 plastic bags make up about 1 ton of plastic waste, so—and this is just a little napkin math—you’d need somewhere in the order of 90 million worms working around the clock for over two weeks to break down a single ton of plastic. In other words, it’s not feasible on a large scale.

That’s why Aspergillus tubingensis is so exciting. If researchers can figure out how to scale the process, we know this fungi offers a rate of plastic degradation that’s fast enough to be viable. And the scale bit? Regular readers already know that fungi can be rapidly propagated (comparative to, say, 90 million wax worms). One has to imagine that this alone would certainly help with the scalability issue.

If you’re interested in learning more about mycoremediation, the book Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World offers countless valuable insights from author Paul Stamets.

➢ It was one of the books featured in our post The Top 5 Fungi Books Every Amateur Mycologist Needs to Have On Their Shelf.